The most important decarbonization chart you’ll see this year

Nat Bullard, the long-time climate writer, consultant and expert who serves on the advisory board for the energy think tank Ember, published his annual decarbonization deck last week, comprising 200 charts illustrating the state of climate tech.

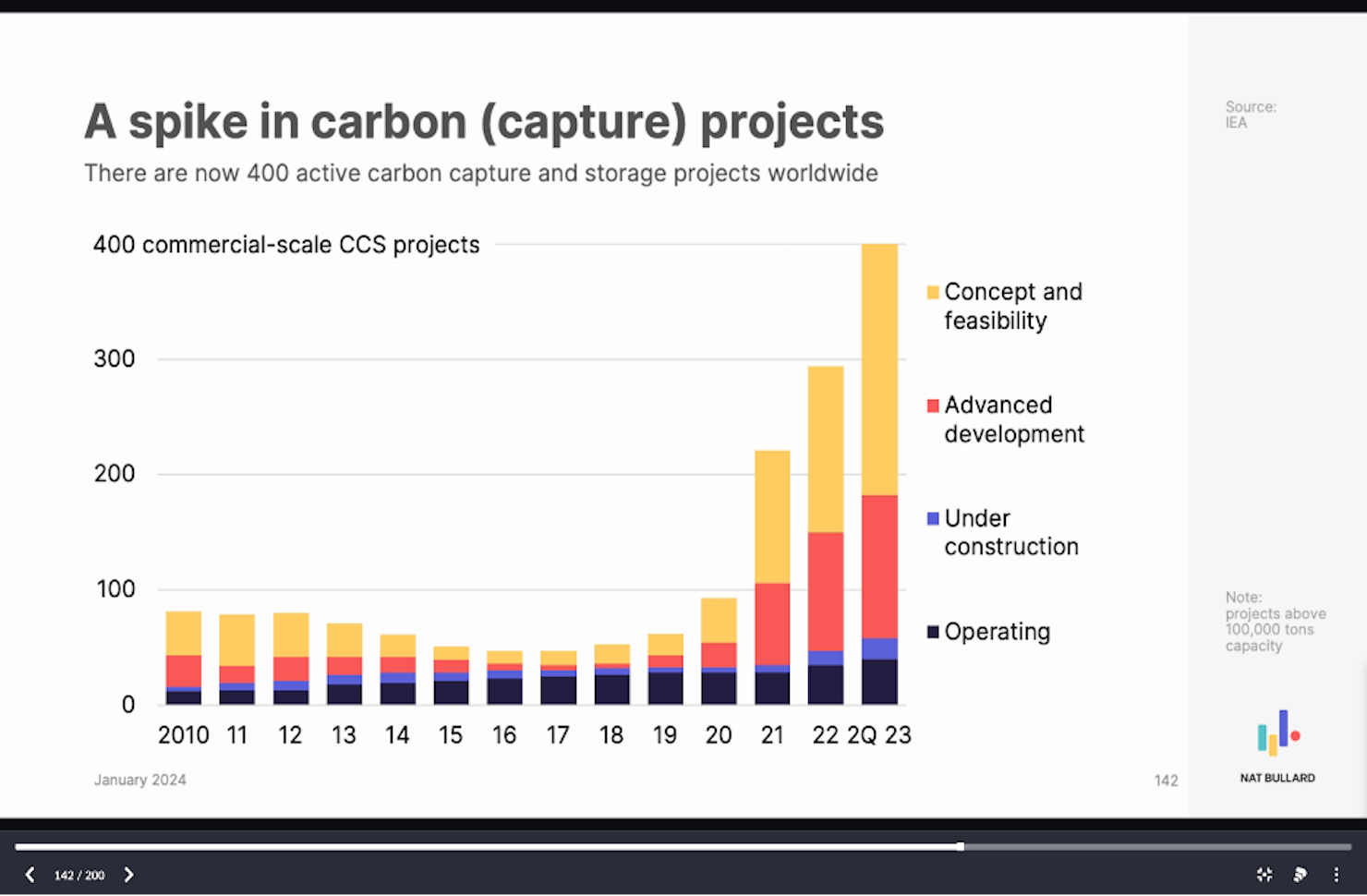

The chart above caught my eye.

Although the title sounds hopeful enough, a closer look at the data is discouraging.

Despite increasingly urgent calls from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for expansion of carbon dioxide removal projects, the number of commercial-scale operating systems has hardly budged in the last six years.

What has grown is the pipeline of projects in the feasibility and development stages. But will these early-stage projects develop fast enough to matter for the climate? The chart suggests that the path from feasibility to operation is a very slow climb.

The good news is that there is a well used playbook for speeding climate tech adoption, and it shows up throughout Bullard’s presentation.

The state of durable carbon removal

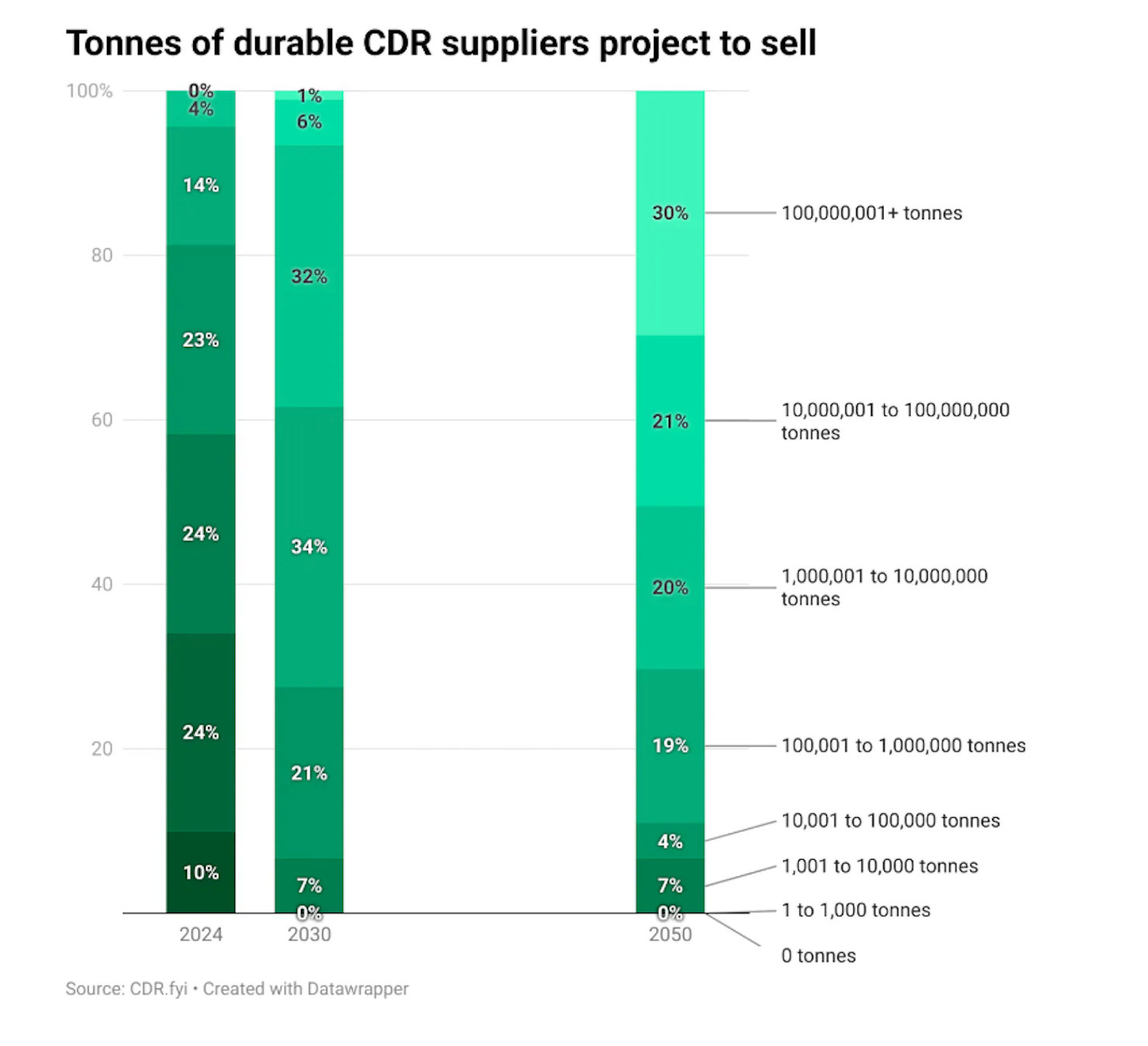

All durable carbon capture projects (ones based on technology rather than nature, such as trees) combined today have removed less than 230,000 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere. That’s far from the nearly gigaton-scale of durable carbon removal many estimates suggest we’ll need by 2030, and 4 gigatons per year we’ll need by 2050, to stay within the goals of the Paris climate accord.

The IEA defines “commercial-scale” as projects capturing over 100,000 tons of CO2 per year. That’s a low threshold in the face of a gigaton-scale problem. The planet would need 10,000 companies to spring up and reach this operating capacity in the next six years to achieve global gigaton-scale removal by 2030.

The good news is that nearly three-quarters of carbon removal operators anticipate they’ll be able to remove 100,000 tons of carbon annually by the end of the decade, according to a recent survey by CDR.fyi. The bad news is that the survey was based on just 91 companies, 1 percent of what’s needed at the 100,000-ton level.

Cost is the highest barrier

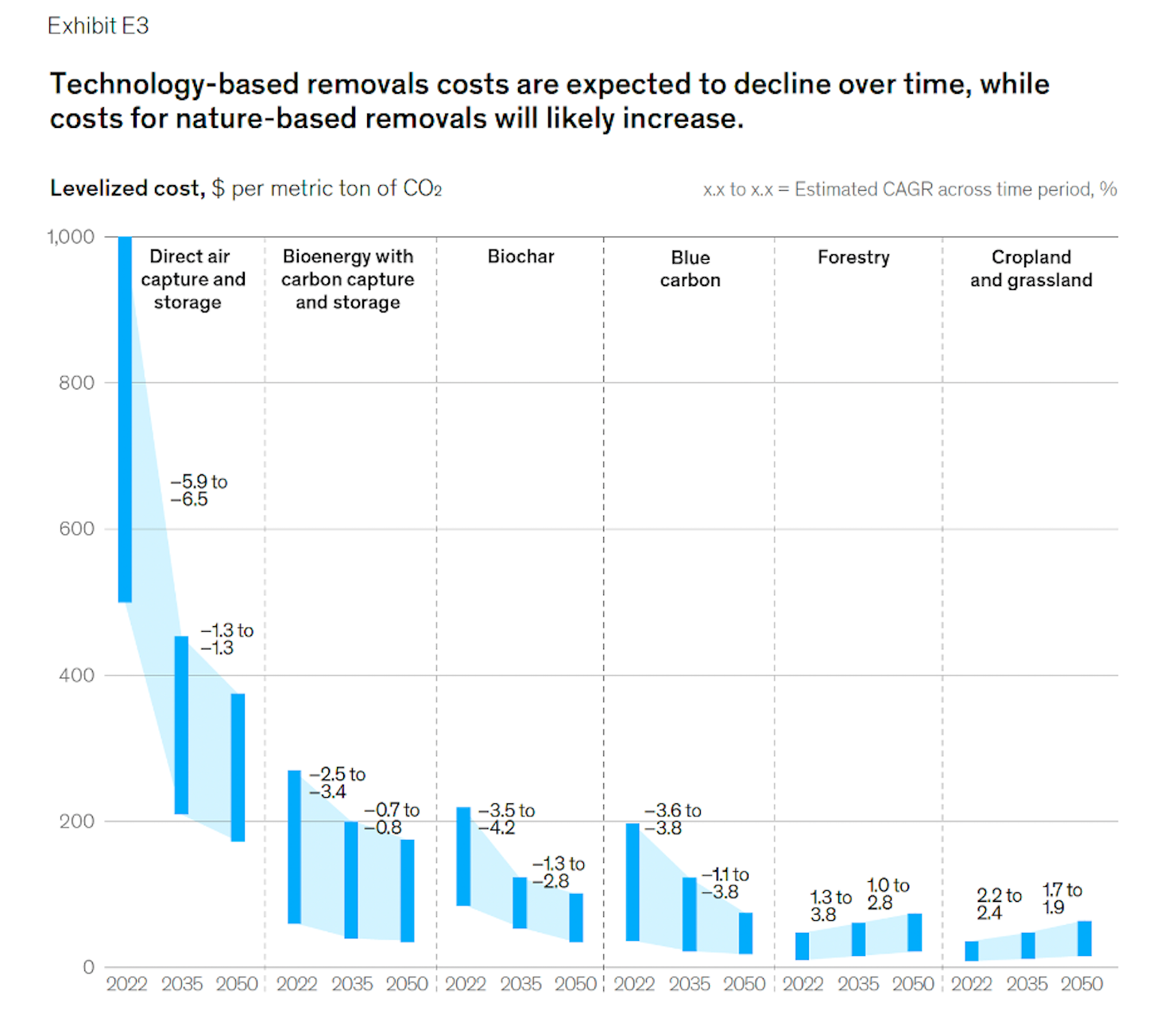

To achieve mass adoption, the costs of carbon removal have to come down. For direct air capture, that threshold is around $200 per ton, comparable with other waste disposal costs, which range from $170 to $205 per ton of solid waste, according to a BCG report.

The costs of direct air capture (DAC) today range from around $600 to $1,000 per ton of CO2 removed from the atmosphere and permanently sequestered. Reducing this to less than $200 per ton would require an 70-80 percent decrease.

While technically possible, the timeframe for such a steep cost reduction is too long. Solar photovoltaic module costs have declined more than 90 percent over the last 40 years. But to limit warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius, we must achieve similar reductions in the costs of carbon capture in 20 years or so. The current policy and investment environment is unlikely to get us there.

We know what to do

A recurring theme in Bullard’s deck is that markets respond to incentives. He provides examples of rapid technology adoption in the renewables sector following financial incentives that range from removal of subsidies for fossil fuels to changes in net metering policies.

The carbon removal industry needs similar incentives to scale up operations and bring down costs.

Capital expenditures for gas turbines, for example, have fallen 15 percent for every doubling in production capacity. If DAC follows a similar learning curve, then an investment of about $200 billion would advance the technology enough to make its costs viable at scale, according to BCG’s research.

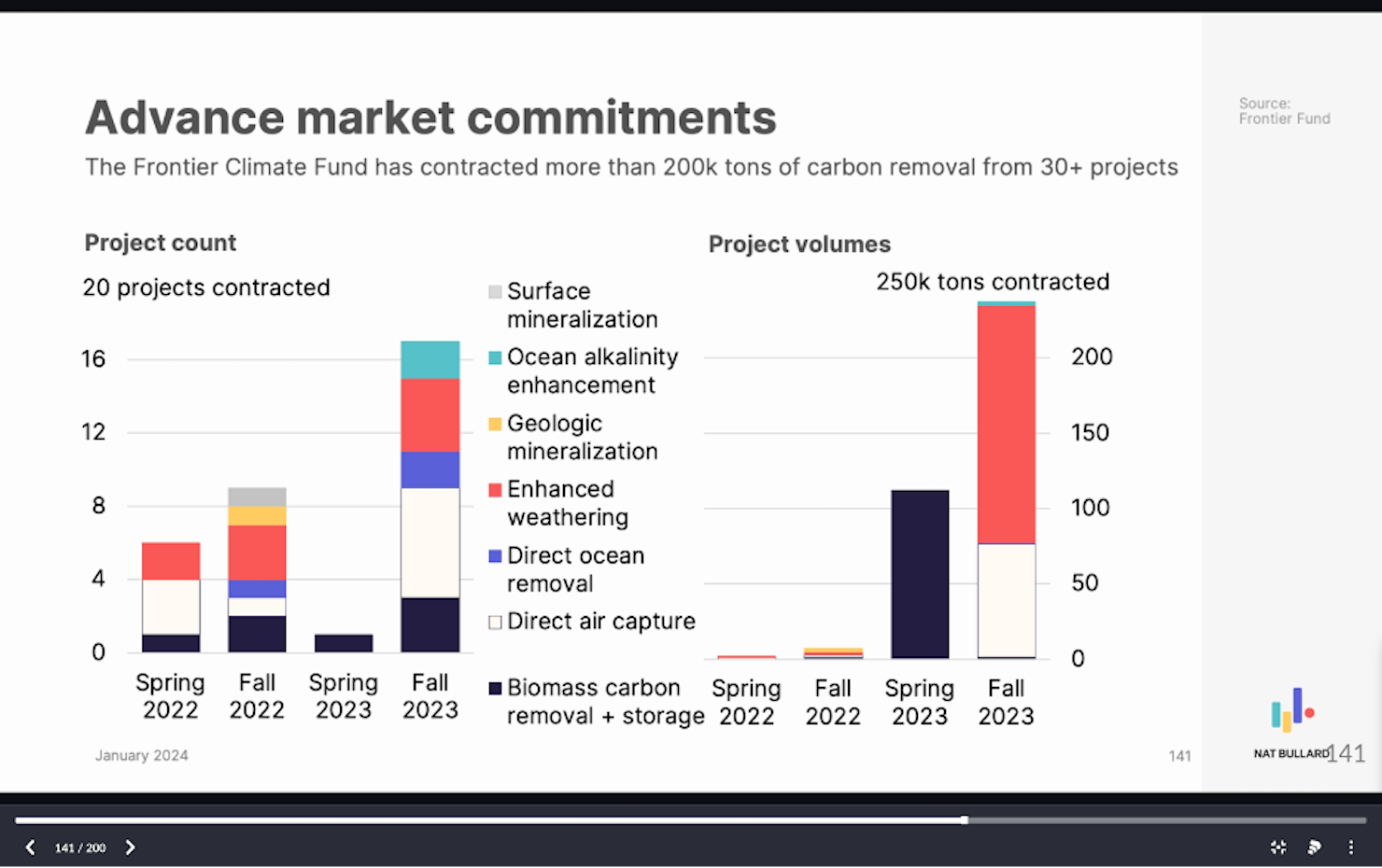

And that investment can come in many forms. Advance market commitments such as the Frontier Climate Fund provide developers confidence to get started, knowing that there will be an end buyer.

Opportunities abound

The $100 million XPrize for carbon removal provides incentives for early-stage companies to take a chance. The evidence that incentives such as this work to accelerate a market is clear: Half of the carbon removal teams competing for the XPrize were founded since the prize launched in 2021.

Tax credits for carbon removal, like those in the Inflation Reduction Act, can further drive down costs and speed up deployment. Other countries including the U.K. have instituted similar incentives for carbon capture research and deployment.

But so far these efforts total less than $3 billion a year.

There are plenty of concrete opportunities to provide the incentives necessary for operating CDR facilities to scale rapidly. One clear opportunity is permitting carbon removals to count as Scope 3 mitigation for companies working on net zero targets. Providing low-cost debt to CDR developers would also help get more capital-intensive projects off the ground.

The post "The most important decarbonization chart you'll see this year" appeared first on Trellis