Combatting Disease and Delays to Build the Panama Canal

First came the French. A syndicate led by Ferdinand de Lesseps, the diplomat who had led construction of the Suez Canal, began excavating a channel through Central America in 1881. Drawing huge contingents of Afro-Caribbean laborers, the workforce peaked at 40,000 in 1888. With approximately 10 ft of annual rainfall in the region, frequent mudslides caused constant setbacks. Malaria and yellow fever killed an estimated 22,000. Waste and corruption by many contractors and suppliers hobbled the effort. Bankruptcy in 1889 resulted in 800,000 mostly middle class French investors losing their holdings.

In the 1890s, U.S. business figures and officials became interested in developing an Atlantic-Pacific canal, with most favoring a Nicaraguan route. After much wrangling, Congress settled on a route in 1902 through what would become the nation of Panama, and agreed to pay $40 million to purchase the French assets: the canal zone concession; the operating Panama Railway, vital to the construction work; and more than 2,000 buildings plus the construction machinery.

President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901 and galvanized the canal effort. He chose Col. William Gorgas, the leading tropical disease doctor in the U.S., to oversee the hospitals and sanitary work. But project leaders dismissed Gorgas’ insistence that rigid sanitary measures had to be implemented before construction ramped up. Gorgas nonetheless proceeded in 1904 to wage war on mosquitos, having recently been identified as transmitters of yellow fever. He trained inspectors to visit every house in the nearby city of Colon to ensure every well, cistern and water jar was covered, and that any pockets of standing water outdoors were coated with oil or kerosene.

The U.S. effort to build the Panama Canal benefitted from earlier abandoned efforts by the French and a concerted attempt by project leaders to eradicate yellow fever in the canal. Figures from ENR archive

As ENR’s editorial endorsement dryly stated, “The best that skill and money can do to improve the sanitary conditions and lessen the risk of epidemics will be well expended, not alone from the humanitarian point of view, but because of an ultimate reduction in the total cost of construction.”

Despite his efforts, project leaders did not take Gorgas seriously, and a 1905 yellow fever outbreak in the canal administration building spurred three-quarters of the Americans to head home. A single stevedore died of bubonic plague, resulting in hundreds of rat traps being set, poison put out, and barracks and ships fumigated.

Chief Engineer John Wallace had let work on the canal progress slowly with the inherited French equipment. Laborers often didn’t have the right tools—railroad spikes were being driven with axes. Secretary of War William Howard Taft, who was in charge of the overall canal effort, summoned Wallace and fired him. A year in, the U.S. canal effort was a disorganized mess.

Wallace’s successor in 1905, John Stevens, was a hardened railroad engineer. He stopped work in the canal’s Culebra Cut for a complete reorganization. To alleviate a housing shortage, he had whole communities built—houses, barracks, mess halls, hospitals, schools and sewage systems. Stevens also gave Gorgas carte blanche to fight disease. Soon Gorgas had 4,000 men working on yellow fever eradication efforts: installing screening, spraying insecticide and applying antiseptics such as carbolic acid. Within 18 months they had brought it under control, allaying the fears of disease that had made it difficult to recruit U.S. workers.

Photo from Wikimedia commons by H.C. White Co., source: The United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs Division, originally posted by Jahoe and available in the public domain via license CC Public Domain Mark 1.0

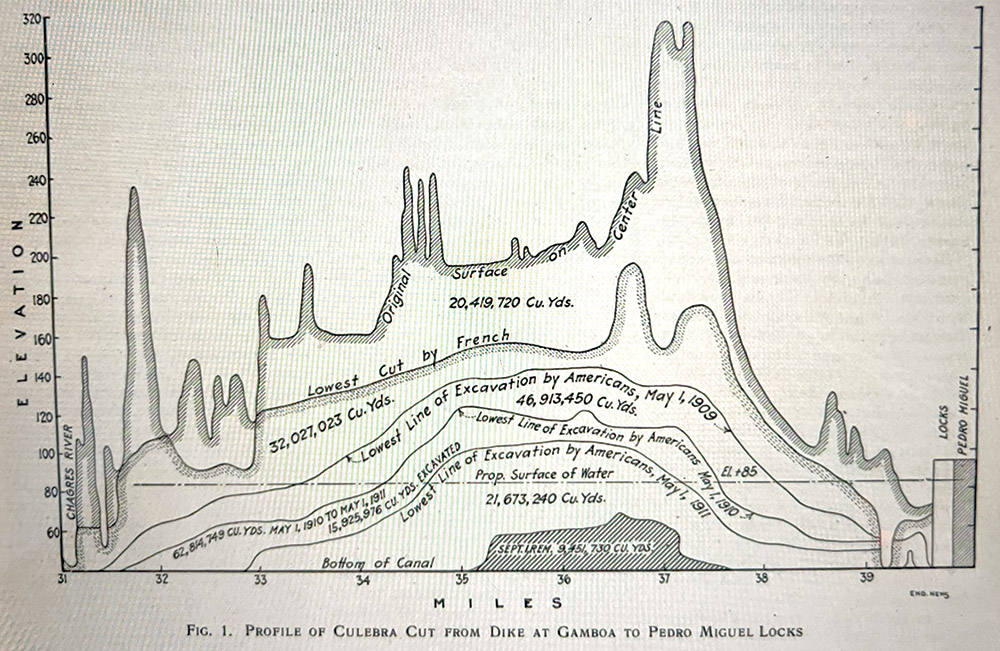

Stevens saw the Panama Railroad as the linchpin. In addition to shuttling workers, food and supplies, it had to transport massive quantities of spoil from the Culebra Cut, a 300-ft-high ridge set to be carved into a nine-mile-long canyon. He replaced the old French rails with heavier tracks and ordered a fleet of massive locomotives, dump cars and 95-ton Bucyrus steam shovels.

Workers from the U.S. were recruited for administrative and clerical work and for the skilled trades. To reduce turnover, married men were encouraged to bring their wives and children and given houses with modern plumbing at no charge. A community took shape, with commissaries supplying American food while churches and schools were set up. Soon there were 6,000 Americans, including 2,500 women and children.

The vast majority of the workforce led a harsher existence. The largest contingent of pick-and-shovel workers was 20,000 men from Barbados. Martinique and Guadeloupe supplied 7,500 laborers and Stevens recruited 8,000 Basques. Laborers dug ditches, cut brush, carried lumber, unloaded boxes of dynamite, and loaded cement. By late 1906 that workforce had reached 24,000.

Initially laborers were assigned tents and fed in mess halls where they found the food substandard. Mess halls, housing and hospitals were all segregated. Most ended up leaving the camps and renting rooms in the slums of Colon or Panama City. Many built their own shacks in the bush. Black laborers, enduring inferior living conditions and more dangerous assignments, had a death rate four times that of whites. Although yellow fever had been vanquished, many workers succumbed to pneumonia, typhoid fever and various intestinal diseases. Canal authorities made no provisions for the thousands of workers who were maimed.

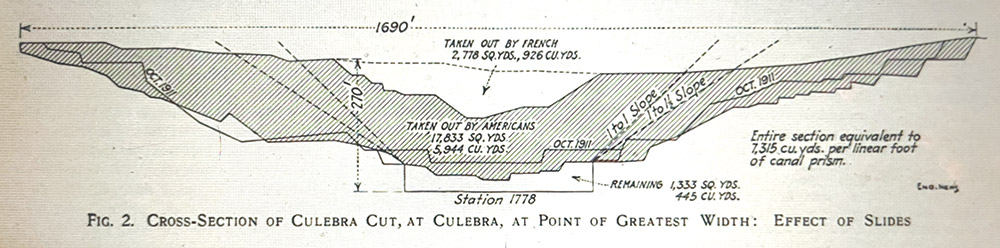

The Culebra Cut was the intimidating challenge. The French effort had excavated 78 million cu yd of earth and rock, but only 30 million cu yd of that lay within the final canal route. Stevens’ plan of attack was akin to surface mining: lay sets of parallel tracks at various levels along the sloping sides of the cut. Rail-mounted steam shovels on the uphill track chewed into the slope and deposited spoil onto flat cars waiting on the downhill track. Trains of empty cars ran like a gigantic conveyor belt.

Although long-planned as a sea-level channel similar to the Suez Canal, some engineers who studied the route argued that landslides and the Chagres River’s violent floods posed dangers, and ships moving at higher speeds in excavated channels were more likely to run aground than in a lock-and-dam system. After much study and dispute, the lock-and-dam view won out, approved by the Senate in close vote in 1907.

In two years Stevens had stabilized and reorganized the project, making remarkable improvements in housing, health and supply, mobilizing both men and machinery. He resigned suddenly in 1907 without giving a reason. Roosevelt quickly appointed George Goethals, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers standout, as chief engineer, giving him near-dictatorial authority to eliminate bureaucratic headaches. He was cool-tempered and rigorous. Early in his tenure steam shovel engineers threatened to strike and walked off the job. Goethals fired them and hired new crews. He treated workers humanely, dedicating Sunday mornings to hearing workers’ grievances on a first come, first served basis.

Figure from ENR archive.

By 1909 there were 68 steam shovels at work in the cut, 500 trainloads of spoil a day were carried away, and the workforce had reached 44,000. Three hundred drillers were at work with dynamite crews placing 800,000 sticks of dynamite in the holes each month. The 76 miles of terraced tracks within the cut had to be relocated repeatedly as excavation progressed. Drilling, blasting, shoveling, dirt hauling and track shifting all had to be coordinated. Much of the spoil was used to build embankments or the 3.3-mile-long Naos Island breakwater protecting the Pacific Ocean canal entrance.

The lock and dam design meant the Gatun Dam had to be sited further downstream and grow in size: 115 ft high and 7,700 ft long. It would create the largest artificial lake in the world, Lake Gatun, flooding 166 sq miles and displacing 40,000 Panamanians. Lack of bedrock at the dam site raised concerns, but it was ultimately deemed safe. The dam has a core of impermeable blue clay, and its volume of 22 million cu yd made it the largest earthen dam in the world.

The six pairs of locks were and are imposing monoliths: 110 ft wide, 1,000 ft long, with the tallest chambers 81 ft. They were constructed by pouring concrete from overhead cableways into huge forms. Within the side walls, 18-ft-dia tunnels carried the water used to fill the locks. The steel lock gates were the largest ever erected: 65 ft wide, 47 to 80 ft tall, and 7 ft thick. Fifty mills, foundries and specialty fabricators in Pittsburgh supplied most of the lock components.

Landslides were a regular threat. The Cucaracha slide in 1907 saw 50 acres of slope slip downwards over 10 days. The 500,000 cu yd of mud dumped into the canal buried rail tracks and two steam shovels.

The Panama Canal opened in 1914, rewiring global trade. A decade of U.S. efforts had excavated 232 million cu yd of material. But it came at a great cost, with 5,609 workers dead from disease and accidents.

The post "Combatting Disease and Delays to Build the Panama Canal" appeared first on Consulting-Specifying Engineer