The 1990s: Green Takes Off and Facility Managers Surf the Web

The arrival of ADA requirements and phasing out of CFCs also impact facility management.

However, renovations quickly became a top priority for every facility manager as the American Disabilities Act (ADA) is signed into law by President George Bush in July 1990. Retail establishments, restaurants and commercial offices were now required to be accessible to people with disabilities – roughly 43 million Americans at the time – provided the cost of ensuring accessibility is not too excessive.

According to the law, any alterations to a space after Jan. 26, 1992, must be accessible and usable by individuals with disabilities. Some simpler things building owners and facility managers were expected to do included installing ramps, installing flashing alarm lights, widening doors, repositioning restroom dispensers, raising toilet seats, cutting curbs in sidewalks and entrances, rearranging furniture, and adding braille to signage.

When ADA was first announced, there was concern over the vagueness of the law regarding building owners’ responsibility, but the legislation was intended that way. ADA continues to be enforced on a case-by-case basis through the courts.

“Building owners can’t sit around and hope the guy down the block gets sued first,” says Jim Dinegar, vice president for government and industry affairs for BOMA in a 1992 article.

In March 1993, the first formal out of court settlement for an ADA case was resolved by the Department of Justice. The case involved failure to remove architectural barriers at a bank.

By 1993, ADA is the No. 1 reason for modernization, the first time in nearly a decade renovations weren’t done for energy efficiency purposes. However, energy quickly becomes a focal point again thanks to advances in lighting technology.

By changing lighting to T8 lamps and electronic ballasts, facilities experienced electricity savings of up to 43 percent compared to using common T12 lamps and magnetic ballasts. Rebates and low interest rates help fuel interest in energy saving retrofits because payback is so quick with the extra incentives.

Although money was likely the primary driving force behind the changes, sustainability and helping the environment was marketed as a bonus. New environmental programs popped up during the decade, such as the GreenLights Initiative from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1991.

GreenLights was the first voluntary climate initiative, encouraging facility managers to run their buildings with energy-efficient lighting technology. After one year, more than 650 organizations had signed on, representing 3 billion square feet of space, roughly 4 percent of the national total. Within two years, the number of organizations participating more than doubled. Companies in the program saved $23 billion in electricity costs in less than five years.

Following the success of this program, the Energy Star Buildings Program launched in 1995 to help building owners increase efficiency of their buildings’ mechanical and electrical systems. By following a 5-stage strategy, energy expenditures could be cut in half.

In addition to government programs, green came to the forefront thanks to the formation of the U.S. Green Building Council in 1993. A few years later, USGBC introduced its LEED rating system for new buildings and major renovations (which would officially launch in 2000 after years of testing). It was the first time U.S. buildings had a definition of environmental impacts from building products, construction materials, and how it is serviced. And just like other programs, building owners perked up when they learned about the cost savings these green buildings provided.

“Green buildings can offer a number of advantages, not the least of which is capital and lifecycle cost savings that make the project competitive, and in some cases, less expensive to build and operate,” wrote the USGBC in the special Green Building Report, which appeared quarterly in the magazine.

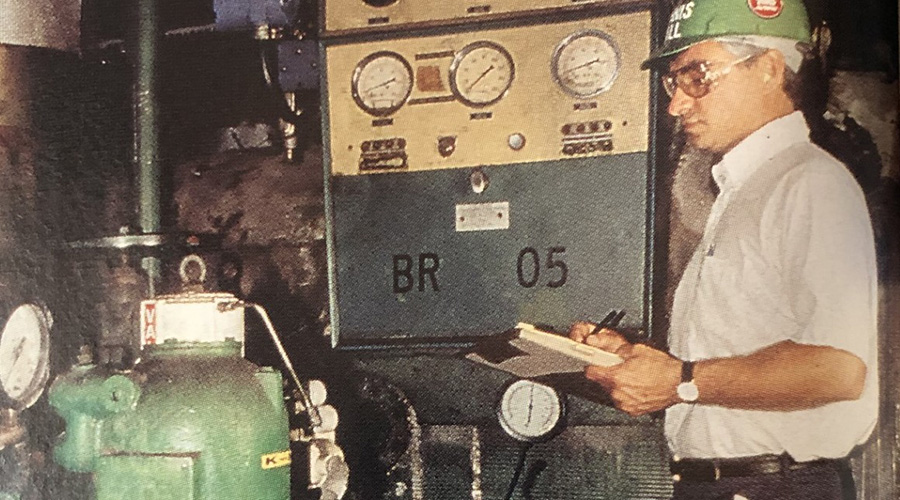

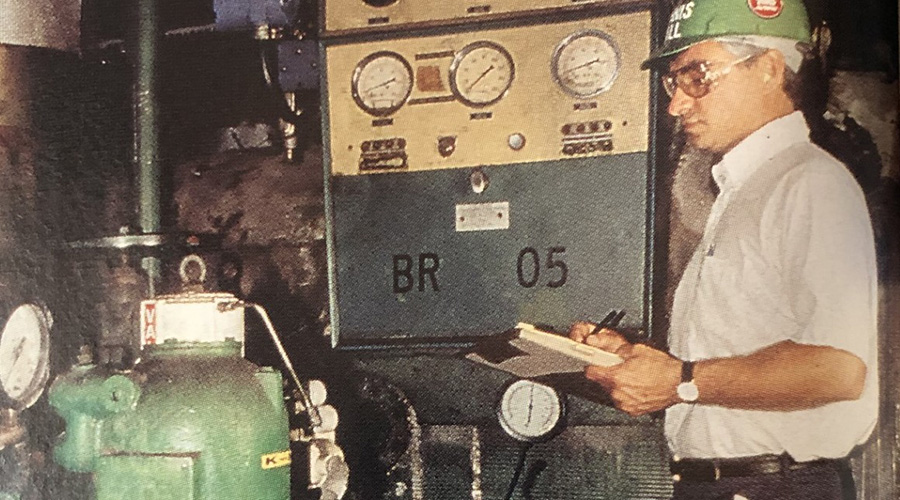

Energy efficiency and green buildings weren’t the only environmental initiatives during the decade. To protect ozone depletion, chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) was banned in 1994, and to be phased out to alternative refrigerants like hydrofluorocarbons (HCFs). These, too, would be phased out after 2016.

More than 80,000 chillers in the U.S. used CFCs as refrigerants at the time. As they were phased out, there was a fear of shortages and every year supply was scrutinized. Costs of CFCs increased as taxes imposed on them increased and supply diminished. Despite building owners’ concerns, the phase out happened with few problems.

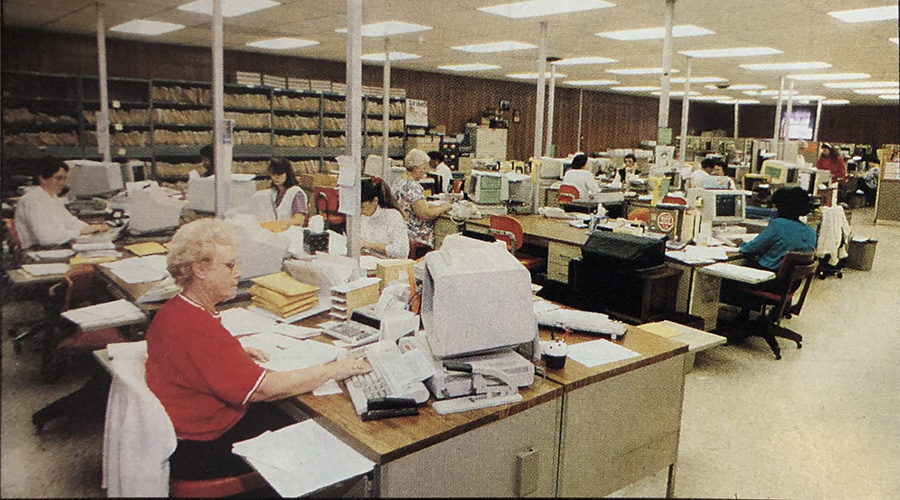

Personal computer use had been continually increasing each year through the 1980s as they became cheaper. With the rapid rise in technology, more software programs became available for the facility management profession and the term computer aided facility management – or CAFM for short – was born. This new moniker for automation now put software under one roof so different departments could share data and create efficiencies. CAFM could mean space needs analysis, space planning, cost accounting or a whole suite of systems.

“CAFM is any type of software that helps facilities managers do their job,” says Peter Kimmel, president of Peter S. Kimmel and Associates in a 1991 article.

As software programs rose in prominence, so did another computer technology – the Internet. The “information age” brought new potential for facility managers, but also problems they hadn’t encountered before, namely cabling and cybersecurity. Just like personal computers before it, more and more facility managers used the Internet each year for industry news, product information and networking.

Even Building Operating Management launched its website, FacilitiesNet, in September 1995. Included on the site are interpretations of government regulations, job postings, networking portal, online Buyer’s Guide, and, of course, the latest issue of the magazine.

“The Internet makes it easy to build and maintain relationships. It’s a great tool for eliminating communication barriers and the line between internal and external groups,” says Steve E. Moskowitz, director of facilities and planning for Conoco Inc., in a 1998 article.

As the clock turned from 1999 to 2000, facility managers began to become concerned about Y2K and its impact on building automation systems, elevators, fire protection systems, and access control systems. For example, an access control system that is not yet Y2K compliant could either lock everyone out of the building or allow anyone to enter.

Unsure of what to expect, facility managers were encouraged to program the clocks ahead to see what would happen and take action accordingly. According to a FacilitiesNet poll, 98 percent of facility managers were concerned Y2K would affect computer systems, 84 percent were concerned about the HVAC system and 80 percent about the security system. Thanks to the preparation, the Millenium ended with little Y2K fanfare.

Throughout the decade, as facility managers grappled with new accessibility requirements, embraced new environmental initiatives and boldly surfed the World Wide Web, they also had to keep an eye on the security of their buildings and the safety of the occupants within.

In 1993, the bombing of the World Trade Center made international terrorism a legit concern. Two years later, the Oklahoma City bombing added domestic terrorism as a high-profile threat.

“The bombing of the Murrah Federal Building set off terrorists inspired to do the greatest amount of damage to the greatest amount of people,” wrote managing editor Mike Lobash in a 1999 article.

In the latter half of the decade, terrorist threats increased every year and government buildings weren’t the only targets. TV stations, abortion clinics and human right organizations also were concerned over the growing violence. Sadly, at the end of the decade, another type of facility would be added to this list: schools. The Columbine shooting in 1999 would make security and safety an even greater concern for facility managers as the decade came to an end. And for all their efforts, few could fathom the atrocities of 9/11, just ahead.

By Dan Weltin, Editor-in-Chief

Dan Weltin is the editor-in-chief of the facilities market. He has more than 20 years of experience writing about facility-related issues.

The post "The 1990s: Green Takes Off and Facility Managers Surf the Web" appeared first on Building Operating & Management