Ethiopia Inaugurates $5B Renaissance Dam, Africa’s Largest Hydropower Project

Ethiopia officially inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam Sept. 9, marking completion of a 14-year, $5-billion roller-compacted concrete gravity dam project on the Nile River that now ranks as Africa’s largest hydroelectric facility and a source of national pride—and regional tension.

In remarks carried by state media, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed hailed the event as “a symbol of Ethiopia’s renaissance,” adding that the dam “is not built to harm Egypt or Sudan but to light up our homes, power our factories and integrate our region,” according to a Reuters pool report. The ceremony was also attended by Pietro Salini, chief executive of Webuild Group (formerly Salini Impregilo), which designed and built the project.

Engineering and Delivery

The dam rises about 145 m above the riverbed and stretches 1,780 m across, with a structural volume exceeding 10 million m³ of roller-compacted concrete, according to data published by the Ministry of Water and Energy and Webuild.

The company says GERD is the largest RCC gravity dam ever built in Africa by volume, and that on Dec. 28, 2014, its crews set a world record by placing 23,000 m³ of RCC in 24 hours. Its reservoir—one of the world’s largest—has a storage capacity of 74 billion m³, flooding an area of roughly 1,874 km² at full pool.

When all 13 Francis turbines are commissioned, GERD will generate up to 5,150 MW, equal to the output of three medium-sized nuclear reactors, with an expected annual generation of 15,700 GWh, according to an emailed statement to ENR by Webuild.

Six turbines were already in operation at the time of inauguration, according to the Financial Times, which reported that “all of them will be used” following the Sept. 9 ceremony. African Energy, citing two sources familiar with the project, also confirmed that all units are expected to be ready for full commercial operation “imminently.”

Construction on the project began in 2011 with an initial budget of $4.8 billion. The scope grew as design changes and additional electromechanical systems were incorporated, bringing the final price tag to approximately $5 billion. Civil works included saddle dam redesigns and spillway upgrades, while turbine installation and commissioning are ongoing.

The project’s lead engineer, Simegnew Bekele, a state employee, had been the public face of the project, managing the early stages until he was murdered in July 2018. His death sparked widespread grief and outrage, ENR reported at the time, as well as raised questions about whether it was connected to the power project owned by the state utility Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation (EEPC).

Bekele described GERD as “the manifestation of Ethiopia’s determination to develop with our own hands,” in a statement posted by EEPC at the time of the dam’s mid-point construction. Successive managers carried the project through Blue Nile diversion, roller-compacted concrete placement and reservoir filling, which began in stages starting in 2020.

Unlike most global megadams, GERD was built largely without multilateral bank funding. The government says 91% of the $5 billion cost was financed domestically through bonds, payroll contributions and public fundraising.

Only about $1 billion—covering turbines and electromechanical systems—was provided by China’s Exim Bank. “GERD is unique not only for its scale but for being self-financed by Ethiopians,” said Minister of Water and Energy Habtamu Itefa in a briefing published by the ministry earlier this year.

Webuild emphasized the human scale of the job, noting that more than 25,000 people—mostly Ethiopians—worked on the dam over 14 years: “A new town has emerged around the site, with a hospital, schools, clinics, roads and a bakery,” providing lasting infrastructure for the surrounding region.

* * *

Power, Pride and Pressure

State planners see GERD as the linchpin of an electrification push aimed at reaching universal domestic access by 2030 while positioning Ethiopia as a regional exporter.

Ethiopian officials say agreements are already in place to transmit power to Sudan, Djibouti and Kenya. “GERD offers the prospect of shared development if our neighbors choose cooperation,” Abiy said in his inauguration speech. However, that prospect remains contested.

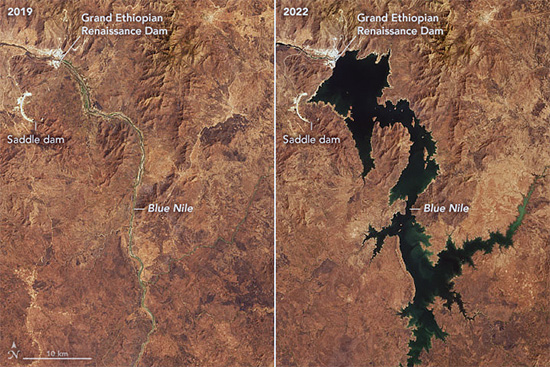

Side-by-side satellite images of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the Blue Nile. (The Feb. 6, 2019, photo shows the river before impoundment, while the Feb. 22, 2022, image shows the reservoir filled behind the dam.) Image courtesy of NASA.

Side-by-side satellite images of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the Blue Nile. (The Feb. 6, 2019, photo shows the river before impoundment, while the Feb. 22, 2022, image shows the reservoir filled behind the dam.) Image courtesy of NASA.

With little rainfall of its own, Egypt depends on the Nile for nearly all its freshwater and has warned that unilateral filling and operation of GERD could threaten its water security. Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry said in a statement issued by Cairo on Sept. 9 that “Egypt will not accept measures that endanger the lives and livelihoods of 100 million citizens.”

Egypt’s concerns stem from its position at the far downstream end of the Nile system. The Blue Nile, which rises in Ethiopia’s highlands, contributes about 60–70% of the river’s total flow by the time it reaches Aswan. As GERD’s reservoir fills and later regulates seasonal discharges, the volume and timing of water available to both Sudan and Egypt could be altered.

Sudan has also raised concerns about uncoordinated water releases and potential safety risks. While the 2015 Declaration of Principles committed Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan to negotiate operating rules, no binding agreement has yet been reached.

Ethiopian officials counter that reservoir filling has not caused major downstream disruption. “We have managed [to fill] in a manner that balances our needs with the flow to our neighbors,” Habtamu said in July, according to ministry transcripts.

Beyond geopolitics, GERD stands as a landmark feat of dam engineering. Its sheer scale places it in the company of the world’s largest hydro projects, with roller-compacted concrete volumes rivaling China’s Three Gorges Dam.

Sediment-management designs and safety reviews by international experts were incorporated into the final structure, according to the ministry. For Ethiopia’s construction sector, the project has trained thousands of workers in RCC techniques, hydro-mechanical installation and high-voltage transmission—skills that are already being applied to follow-on infrastructure.

With its inauguration, GERD shifts from an aspirational build to an operating asset capable of reshaping East Africa’s energy landscape. “This is not just a dam,” Abiy said at the ribbon-cutting. “It is the cornerstone of Ethiopia’s future.”

For contractors and engineers, the project offers lessons in scale, self-financing and delivery under extraordinary political and logistical pressures. “With GERD, Webuild reaffirms its global leadership in delivering large-scale, complex and sustainable infrastructure,” Salini said in a statement.

The post "Ethiopia Inaugurates $5B Renaissance Dam, Africa’s Largest Hydropower Project" appeared first on Consulting-Specifying Engineer