Most of us know that the relative humidity (RH) in a mechanically ventilated building should be maintained between 40 and 60 percent. Most of us are pretty careful about that upper limit of 60% but what about the lower limit of 40%?

An article back in 2015 cited a study done by an Indoor Air Quality expert in the New York area, where data was collected in all 4 seasons and analyzed from over 125 different “Class A” commercial buildings over a 5 year span.

“A significant difference in indoor RH levels with regards to the seasons was noticed. In the spring and summer months, RH levels were found to average nearly 42 percent. In the fall and winter months, though, RH levels averaged under 29 percent, with over half of all the readings below 30 percent and levels as low as 9 percent recorded in some buildings.”

Low RH levels have been reported to increase the incidence of upper respiratory infections and to increase the viability of viruses. They may also encourage the transmission of viruses.

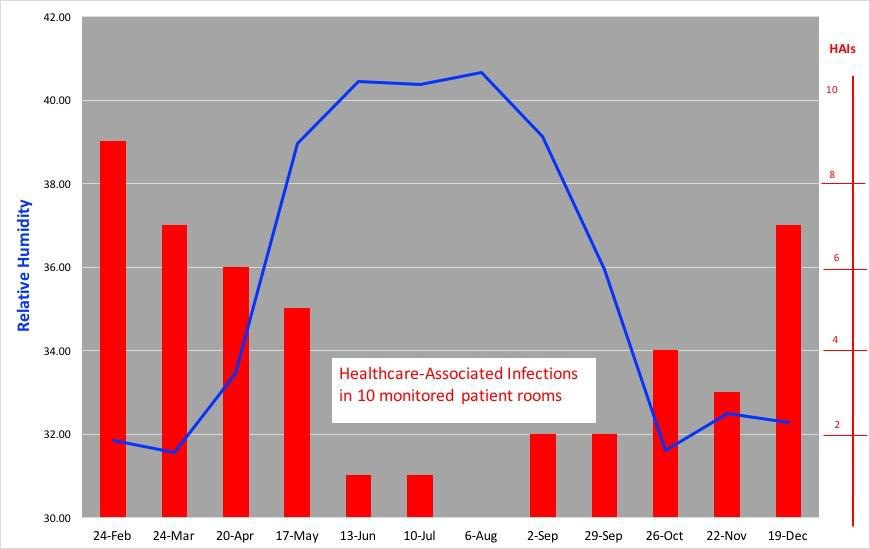

Back in 2016. I attended an excellent presentation at the Washington State Society for Healthcare Engineering  delivered by Dr. Stephanie H Taylor MD, M Arch, CIC. The presentation was entitled “Ventilation and Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs). As you might imagine from the title, much of it was technical in nature. Yet a few key points stood out to me as being applicable to a broad range of buildings. The figure here on the relationship between HAIs and RH levels is one of them. Note the correlation with the study done on office buildings cited above? Of interest to me also was the fact that relative humidity (at the low end) is frequently not managed except in a few critical spaces within many hospitals and other care facilities. Of course the same is true for office buildings as well.

delivered by Dr. Stephanie H Taylor MD, M Arch, CIC. The presentation was entitled “Ventilation and Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs). As you might imagine from the title, much of it was technical in nature. Yet a few key points stood out to me as being applicable to a broad range of buildings. The figure here on the relationship between HAIs and RH levels is one of them. Note the correlation with the study done on office buildings cited above? Of interest to me also was the fact that relative humidity (at the low end) is frequently not managed except in a few critical spaces within many hospitals and other care facilities. Of course the same is true for office buildings as well.

What with the recent significant number of outbreaks of covid-19 at nursing homes and residential care facilities, I suspect we will see similar research about low humidity in those facilities as well.

Yet it seems fairly obvious that low humidity appears to increase the rate of infections.

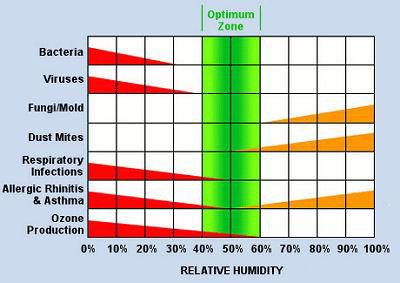

A well known chart detailing this relationship to different types of indoor environmental concerns is shown in  the next graphic. As you can see, low humidity is at least as large of a concern as high humidity. In particular, viruses appear to thrive in a low humidity environment.

the next graphic. As you can see, low humidity is at least as large of a concern as high humidity. In particular, viruses appear to thrive in a low humidity environment.

Yet, low humidity is not well controlled in many of our buildings, particularly during the winter months when a minimum amount of outside air is introduced.

Perhaps this is an area that we need to look at significantly with respect to modernization of existing buildings and new construction. If we want to have a healthy environment for our workforce, viability of viruses will be critical to resolve. The same holds true for the environment of care, particularly for the elderly and infirm.

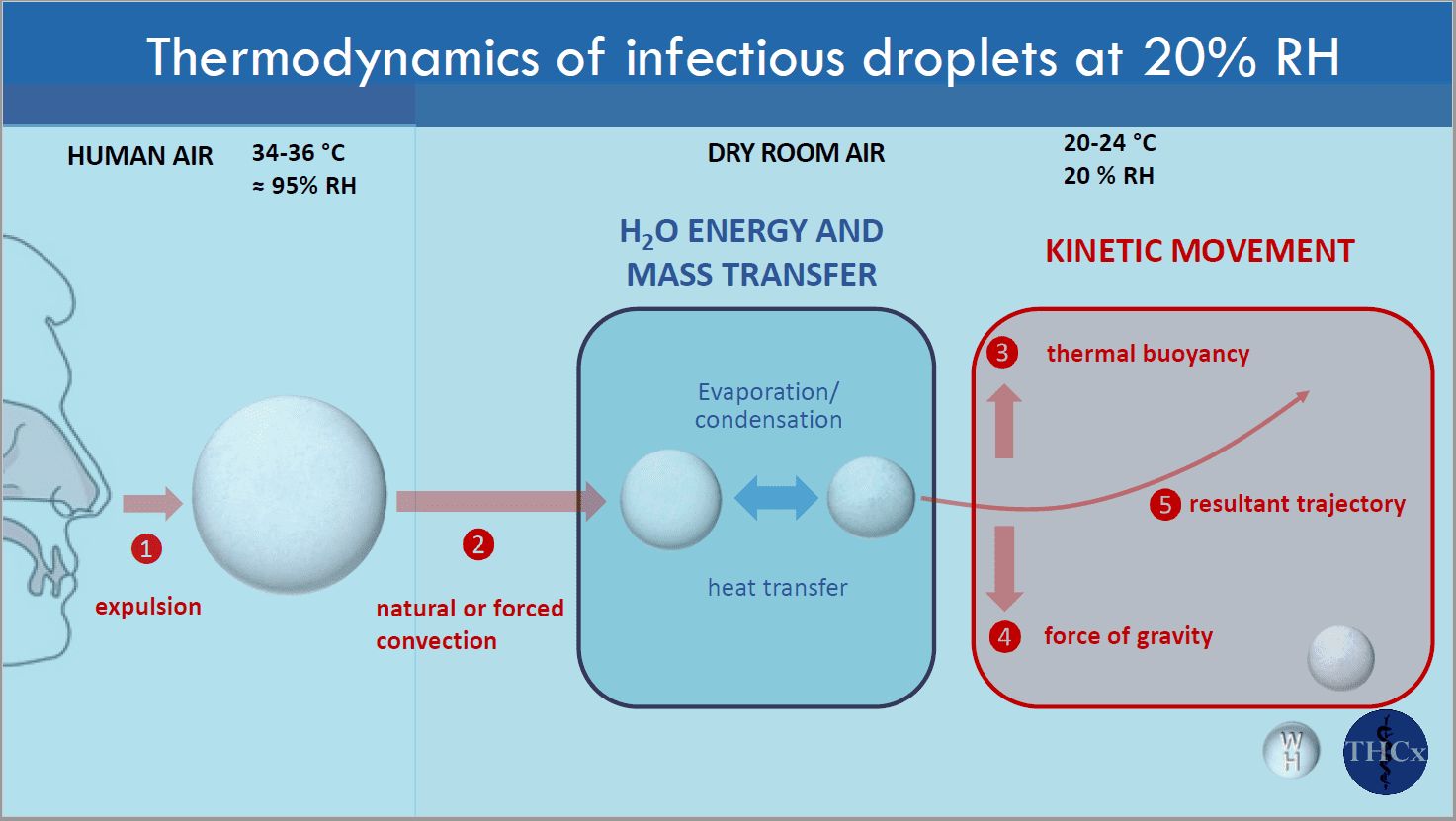

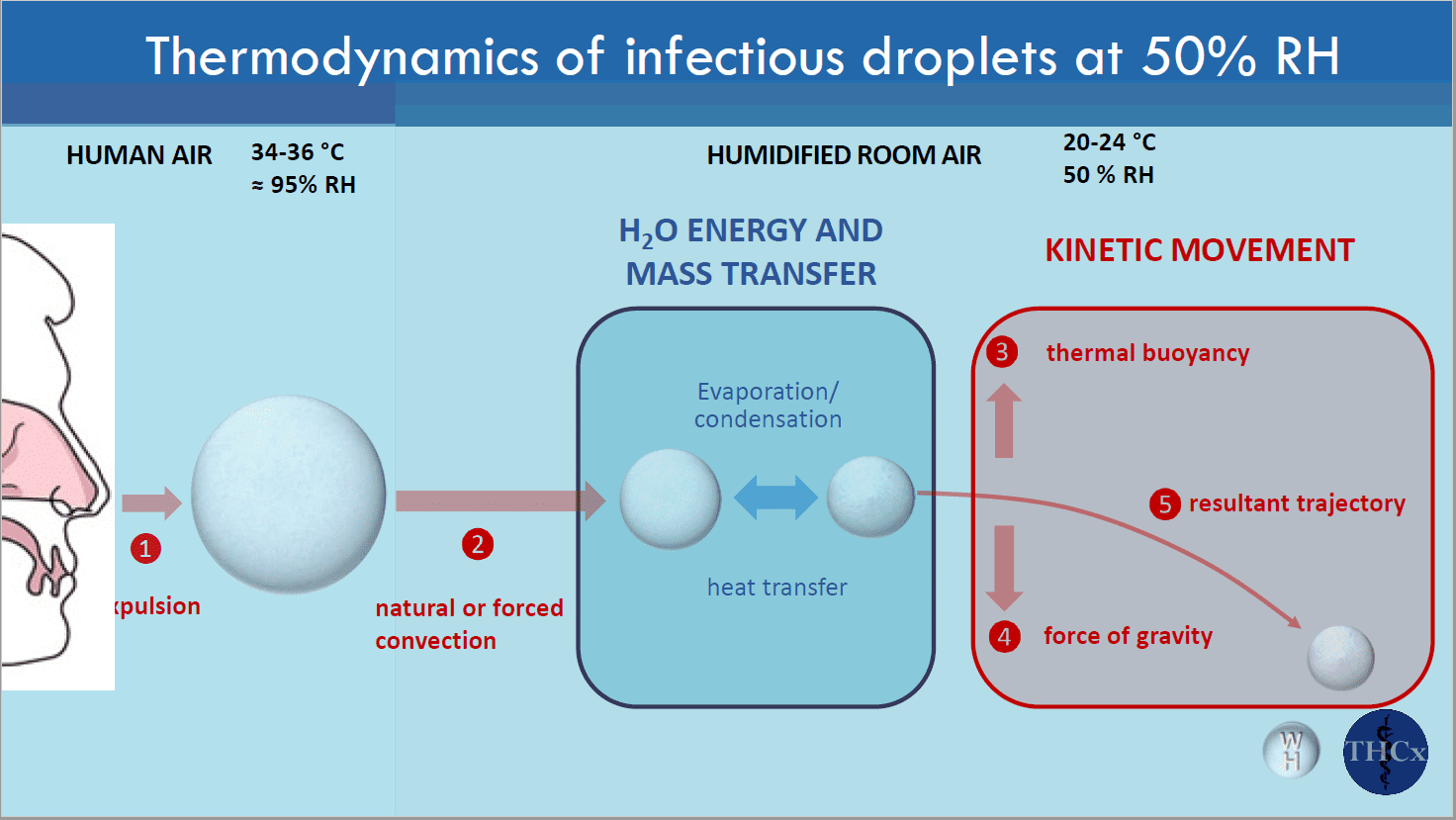

A third key point to make, relates to the transmission of viruses by coughs, sneezes, etc. Essentially we are talking about a particle and its travel in the environment. How is that impacted by humidity? Well again it seems that low humidity has an effect. As the particle travels in the air, it gradually picks up moisture, which increases the droplet size. Once the droplet gets to a certain size, it falls to the floor. Depending on how long this process takes, the travel of the particle is impacted. The two images below show what happens in a low humidity environment, and a normal humidity environment.

I could continue with additional information, however, I think my point is clear. We need to do a better job of managing low humidity in many of our buildings going forward.