Predicting the future is hard. Duh. No one knows which markets are going to be hot in the future. Or when the economy is going to be in recession. Or if there’s going to be another pandemic. Or when a killer app is going to revolutionize our industry. Those are all external factors that you and your leadership team—along with the leadership teams at Disney and Meta and General Electric, etc.—are all trying to guess at how they are going to play out. (The difference is that Disney et al spend a lot more money than you on scenario planning to predict what’s going to happen. Doesn’t make them any smarter, though. They still miss the target as often as they hit it.)

However, when it comes to predicting what lies ahead for your AE or environmental consulting firm, well, there are some surprisingly accurate models available about what you can expect in the future. These are available for you and your leadership team to anticipate “what’s around the corner” as you grow your firm. They are best used to take advantage of “the good times” and to prepare for future inevitable organizational and cultural changes and crises.

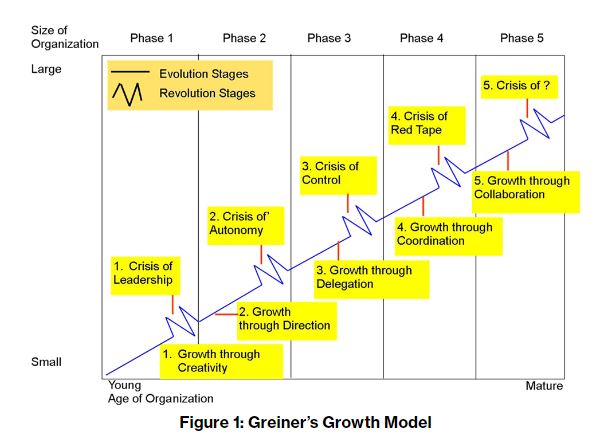

One of these models that I like to use in our strategy work is Larry Greiner’s Growth Model. It’s a really good organizational development model for a professional services firm in a mature, relatively slow-growth industry. “Hey, this Greiner thing was published in 1972, what relevance could it have to today’s tech-enabled AE and environmental business models?” you ask. To which I reply, “What have you got against 1972? Don McLean released both “American Pie” and “Vincent” in 1972, and they’re both as relevant today as they were then.” You then tell me that’s a lousy reply, and I agree. But seriously, Greiner’s model is as robust today for you to reference in your planning for the future as it was 50 years ago. Let’s take a look…

Courtesy: Morrissey Goodale

On the vertical axis is the size of the firm—from small to large. Along the horizontal axis is the age of the organization—from young to mature (we’re not allowed to say “old” apparently). As the firm grows and matures, the model predicts five phases of growth—each capped with a “crisis” that must be navigated to continue growing.

Phase 1: Growth through Creativity: This speaks to the inception and early years of the AE or environmental firm. Those heady days when it’s founded by (typically in our industry) two professionals whose skillsets complement each other. One of them is really good at business development, and one excels at managing projects. One brings home the bacon, and one fries it up and serves it. The perfect yin to the yang. And the firm thrives with that dynamic. It’s nimble; it feels like a “family.” There’s magic in creating something out of nothing. Most firms in our industry are in this phase. They generate somewhere between $5 million and $10 million a year. The founders are making more money than they ever dreamed they could have and are feeling good about where they’re sitting on Maslow’s pyramid. The firm still runs on spreadsheets, QuickBooks, and owner sentiment and personal whim. But it’s working just fine.

Crisis 1: Crisis of Leadership: This crisis occurs when the firm’s growth and associated regulatory (“Wait, I was supposed to fund the 401(k) with actual money?”) and business risks (“I’m not sure our team of 20 full-time employees is really all that qualified to design this $2 billion international airport terminal project that we just won.”) outstrip the management competencies of the founders. The only way to navigate this crisis successfully is by bringing on professional managers in some or all of the functional areas of finance, operations, HR, marketing, and IT. Failure to get through this crisis results in a slow decline with clients and employees abandoning the firm.

Phase 2: Growth through Direction: In this phase, the professional managers establish enterprise-wide systems and processes (read “rules”) to drive efficiencies and manage risk. Classic Business 101. The founders are likely still around, but they have ceded some management responsibilities. The rules and regulations put in place by professional managers represent a “growing up” of the business model. They establish best business practices that are foundational for future profitable growth and expansion to new locations. With this model, the firm can double in size.

Crisis 2: Crisis of Autonomy: I like to call this the “Rebel Yell” crisis. This happens when the project, design, and technical managers push back on the “professionally installed” business systems. (We don’t much like rules, do we?) They consider them in conflict with how best to serve clients and manage projects. This is particularly true for managers who are located in outlying offices. (“Our biggest client in Arizona wants our proposals to look a certain way, but “Marketing” up there in New York City (rolls eyes) keeps using that crummy corporate template. It’s crazy!”) The only way to address this crisis is to grant more decision-making authority to the project, design, technical, and office managers.

Phase 3: Growth through Delegation: Growth is driven by delegating responsibility to client, project, and operations managers. The philosophy is that these specialized managers know what’s best for the company as it pertains to serving a particular client or set of clients, delivering projects, and allocating resources. This in turn allows leaders and professional managers to focus on enterprise strategy and developing systems that support—rather than direct—the specialized managers. This model tends to coincide with the implementation of a multi-faceted profit center or incentive-compensation system (which almost always has a lousy set of unintended consequences—see the next crisis) designed to improve and reward the performance of individual elements of the business. You see this model at play in many multi-office, multi-discipline firms throughout the AE and environmental industry.

Crisis 3: Crisis of Control: This is the “Inmates Are Running the Prison” crisis. “Growth through Delegation” has descended into “Growth through Abdication.” The characteristics of this crisis are plain to see around our industry. Deliverables coming out of the Oakland office don’t look anything like those developed in the San Diego office. Quality controls in the higher education studio are practically non-existent compared with the consistent application of Demings-style systems in the sports studio. Project kickoffs are happening religiously in the structural group while nobody in the civil department can tell you where to find the project management manual. (Don’t even try asking them who is on their project team.) The firm’s insurance providers are now getting spooked as its risk profile is rising dangerously. The only way to navigate this crisis is to “get real” about the core competencies of the business and coordinate activity across the enterprise for the good of the entire firm. No easy or small task. And many AE and environmental firms never make it through this crisis. In many ways, this crisis is fueled by managers looking to “game” their incentive-compensation plans. (Note: This latter point is a huge third-rail issue in the industry. I’ve seen firms implode because of managers trying to maximize their year-end bonuses. It’s a slow-moving train wreck as alpha managers with sizeable equity positions drain the firm for personal gain.)

Phase 4: Growth through Coordination: This phase recognizes that intentional coordination is required across the firm to continue to grow and minimize risk. It’s a repudiation of “every man for himself” and a commitment to “we’re all in this together.” This phase often coincides with a strategic planning effort that is put in place to address the Crisis of Control mess. There is general acknowledgement by managers (although some of it is lip service) that coordination is essential for the good of the entire firm. Meaning that certain managers need to “give up” or “relinquish” some power—or autonomy or compensation (this is where the lip service gets dangerous)—for the greater good. This phase is where you often see the emergence of a Chief Operations Officer in a firm. This person is a direct report to the CEO (if that relationship does not exist, then this phase becomes a disaster) who has legitimacy and standing with both corporate managers and the design, project, and regional managers. She is alternatively called the “Velvet Hammer” or “Ultimate Traffic Cop.” She is trusted by all to look out for the best interests of the firm. She oversees that coordination of business and operations activities designed to optimize results for the entire firm. It’s during this phase that leadership leans heavily on phrases such as “culture,” “shared values,” and “vision.”

Crisis 4: Crisis of Red Tape: In this phase, the good intentions of mission-driven Growth through Coordination and the efforts of the COO are often found on the rocks of bureaucracy. The creation, layering-on, and far too often poor execution of new reports, processes, and functions in the name of leadership-sponsored coordination results in additional “busy” work for employees, which “damages” the firm’s culture. This results in slower decision-making, reduced agility, and diminished ability to respond to market changes while also ushering in a wider loss of efficiency/reduced margins. The severity of this crisis grows the more services, departments, and offices a firm has.

Phase 5: Growth through Collaboration: This is the “Holy Grail” or “Mature” phase. In this phase, everyone in the firm lives and breathes the mantra of owning their own experience, the client’s experience, and the firm’s experience. This is the ideal evolution of Growth through Coordination, one where all parts of the company work together in a trusted, effective manner. Systems are simplified for efficiency; learning and development is championed; and all aspects of the business contribute towards ways to continue success. There is a positive culture around problem-solving. There’s little “red tape,” and processes are simple. Reward is shared on the basis of team performance. Employees feel they can contribute ideas for growth. Everyone knows how they impact the company with the work they do. A common element of firms that are at this phase is that they are leveraging their ERP systems not as a tool “to be used,” but as a core competency critical to continuous improvement.

Crisis 5: Crisis of ? For those industry-leading firms that have mastered Growth through Collaboration, the next crisis is how to continue to grow. Is it through new services? New risk models? Partnerships? Product development? The crisis does not come from within—instead it’s a “better” crisis of picking the right path(s) forward.

Morrissey Goodale is a CFE Media content partner.

Original content can be found at Morrissey Goodale.

The post "Using models to predict the future" appeared first on Consulting-Specifying Engineer

0 Comments