This article begins to lay out the key elements of developing an embedded sustainability strategy. We start with the approach that sustainability must be incorporated into corporate strategy, and not be a stand-alone strategy. That means approaching the sustainability landscape in the same way you approach your business planning — first understand the relevant sustainability trends and associated risks and opportunities. In other words, use the sustainability lens to explore: What are the material ESG issues for our sector/business? What is the competition doing? What behavior and attributes will delight and engage customers? How do we recruit and retain the best employees? Where is regulation going? What type of technologies might help? With whom might we collaborate to meet our goals?

This article will cover the first building blocks in developing an embedded sustainability strategy: mapping your material ESG issues and stakeholders and developing a materiality matrix. You can learn more by reviewing the “Practitioners’ Guide to Embedding Sustainability,” developed by the NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business (CSB).

Identify material ESG factors for the company

The first step is to assess and prioritize the material ESG issues for your company. Material means financially material in the short- and long-term for your company and for other stakeholders such as workers and society. In addition, materiality includes issues that your company significantly impacts and issues that have or could have an impact on your company. For example, an oil and gas company has a material impact on climate change, but climate change will also have a material impact on the company as governments legislate a low-carbon economy and citizens sue energy companies. This happened in the successful class action suit filed in the Netherlands, ruling in 2021 that Shell was “obliged” to reduce (Dutch) the carbon dioxide emissions of its activities by 45 percent at the end of 2030 over 2019 levels.

A seminal study of stock market performance by 2,300 companies over a 20-year period based on their performance on material and immaterial ESG issues found those that performed well on material ESG issues outperformed the others by 6 percent, those that performed well on both material and immaterial issues outperformed by close to 2 percent, those that performed well solely on immaterial issues performed slightly better at .06 percent, and those companies that did not manage for ESG underperformed at minus-2.9 percent. The interesting implication of this research is that managing for all ESG factors results in the company being spread too thin and not performing as well as when it focuses on the material issues. That said, the underperformance of companies that chose to ignore ESG issues, material or otherwise, also provides a cautionary tale.

There are a number of tools for assessing material ESG issues; however, they are in flux as governments get into the act (another reason to get ahead!). Sustainability reporting standards such as the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) are good starting points. SASB is part of the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS), an initiative to set up an International Sustainability Standards Board, which will be the primary global source of information on material ESG issues once operational. There are also standards that provide additional guidance on the materiality of specific topics, such as the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Taskforce for Nature-Based Financial Disclosures (TNFD).

Reviewing what those multi-stakeholder standards have identified as material for your industry sector will provide a helpful preliminary screen. However, this will be the beginning of your work on materiality, not the end.

The first step is to assess and prioritize the material ESG issues for your company. Material means financially material in the short- and long-term for your company and for other stakeholders such as workers and society.

First, the standards are necessarily broad and your business may differ in some part from their analysis. SASB, for example, focuses on areas of interest to investors. The GRI is developed by and for a broader group of stakeholders and includes topics of interest to employees, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), suppliers and so on. Both standards are developed through consensus, which makes the standards more meaningful, but also means they might not include something you have independently determined is material. As such, you should align your materiality analysis with a standard, but be prepared to adjust for the uniqueness of your company.

Second, you will need to prioritize your focus and investments based on your unique business model. Your pathway to diversity and inclusion, for example, will vary based on what your current employee diversity is, what kind of culture you have, the types of positions you have available, and so on.

Third, you will need to reach out to internal and external stakeholders to incorporate their feedback on what is material. Otherwise, you may miss something that an external stakeholder will suggest you should elevate or deprioritize something that your employees, for example, believe should be top priority. Companies may be less comfortable with engaging with external stakeholders, but those stakeholders may have real insight into emerging issues that you would not otherwise take into account.

Fourth, keep in mind that standards are reporting standards, not management standards, so they are process- and output- based, not performance- and outcome/impact-based. The reporting standards combine a view on what is material in the industry (developed through a multi-stakeholder process) with reporting criteria that any one company can report on. Because there is no baseline or benchmarking possible for diverse industries, the standard can identify that chemicals management is important for an apparel company, with criteria confined to tracking chemical use and a policy related to reducing use, but not require a specific chemical reduction or substitution of new technologies. So, a company that has a policy for chemicals management will be treated the same as a company that has developed an innovative manufacturing process that eliminates chemicals, waste disposal costs, and regulatory risks and creates competitive advantage with customers. Obviously, the latter will create value for the company and its stakeholders; the former may not.

Map and engage stakeholders

Understanding stakeholder sentiment is critical for companies today. As companies compete for talent, struggle with community opposition, are targeted by NGOs, and aim to attract long-term investors, stakeholder views on material ESG issues for the company must be considered and incorporated into the analysis. While no company can or should aim to make all stakeholders happy all the time, identifying their material ESG concerns will help manage risk as well as identify potential collaboration partners. Many companies are partnering with NGOs today, for example, in order to improve environmental and social conditions in their supply chains. Their views should also be reflected in the company’s materiality matrix, described below.

Create a materiality matrix

A materiality matrix is the foundation for the company’s embedded sustainability strategy. It combines the company’s internal analysis of material ESG issues for the company with stakeholder perceptions and feedback. It maps the issues onto a matrix with the vertical axis aligned with stakeholder perception of the importance of a given ESG issue and the perpendicular axis aligned with the internal perception of the issue’s importance to business success. The matrix helps prioritize company investment, with the top-right corner being the most important to both the company and stakeholders and an area where the company should focus on excelling. That said, any ESG issue that is mapped anywhere on the matrix is important and should be monitored and managed, although the level of effort may vary. For example, issues in the top-left corner, which are most important to stakeholders but are less important to the company, should be monitored as they may well become more critical over time.

A materiality matrix is the foundation for the company’s embedded sustainability strategy. It combines the company’s internal analysis of material ESG issues for the company with stakeholder perceptions and feedback.

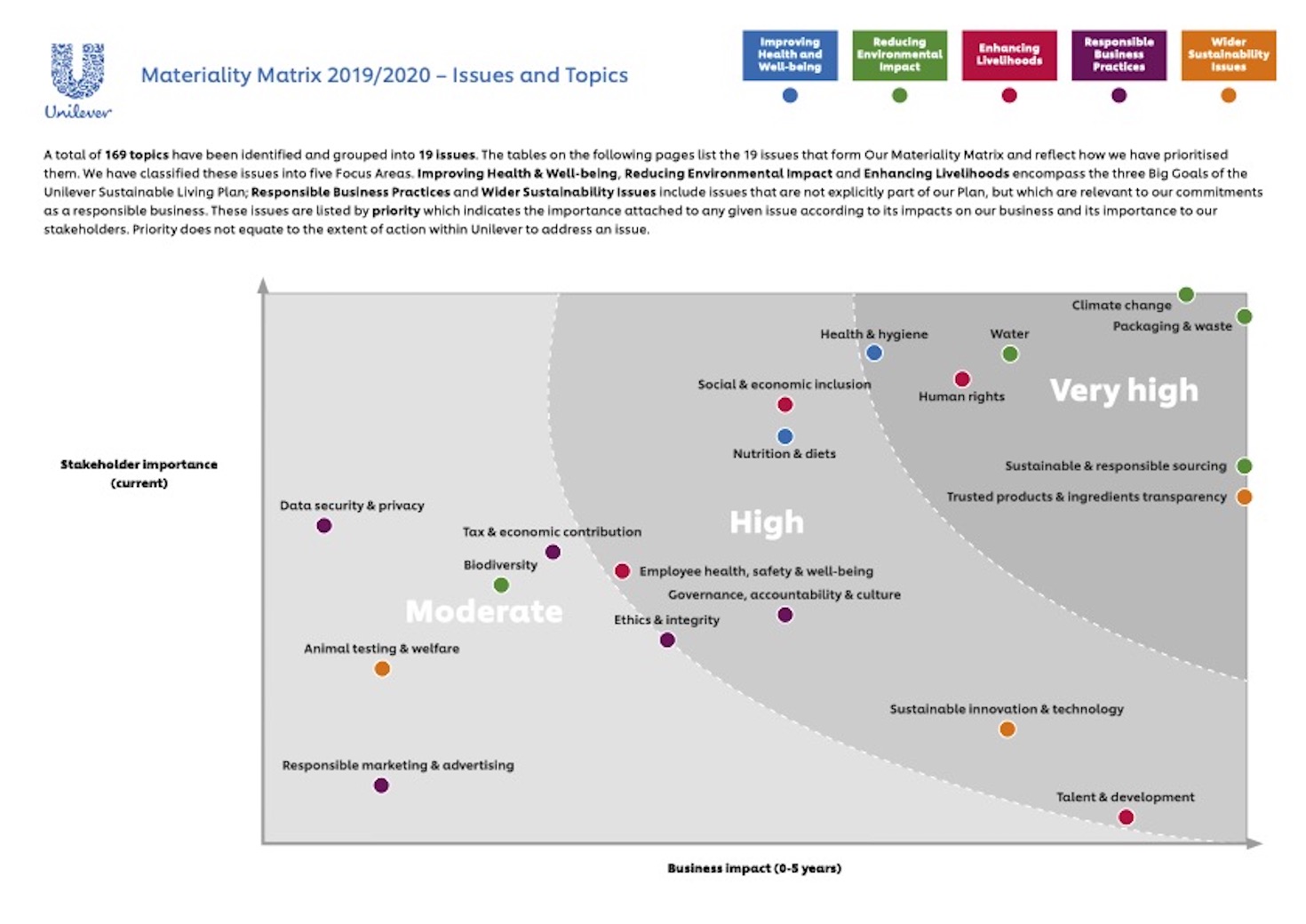

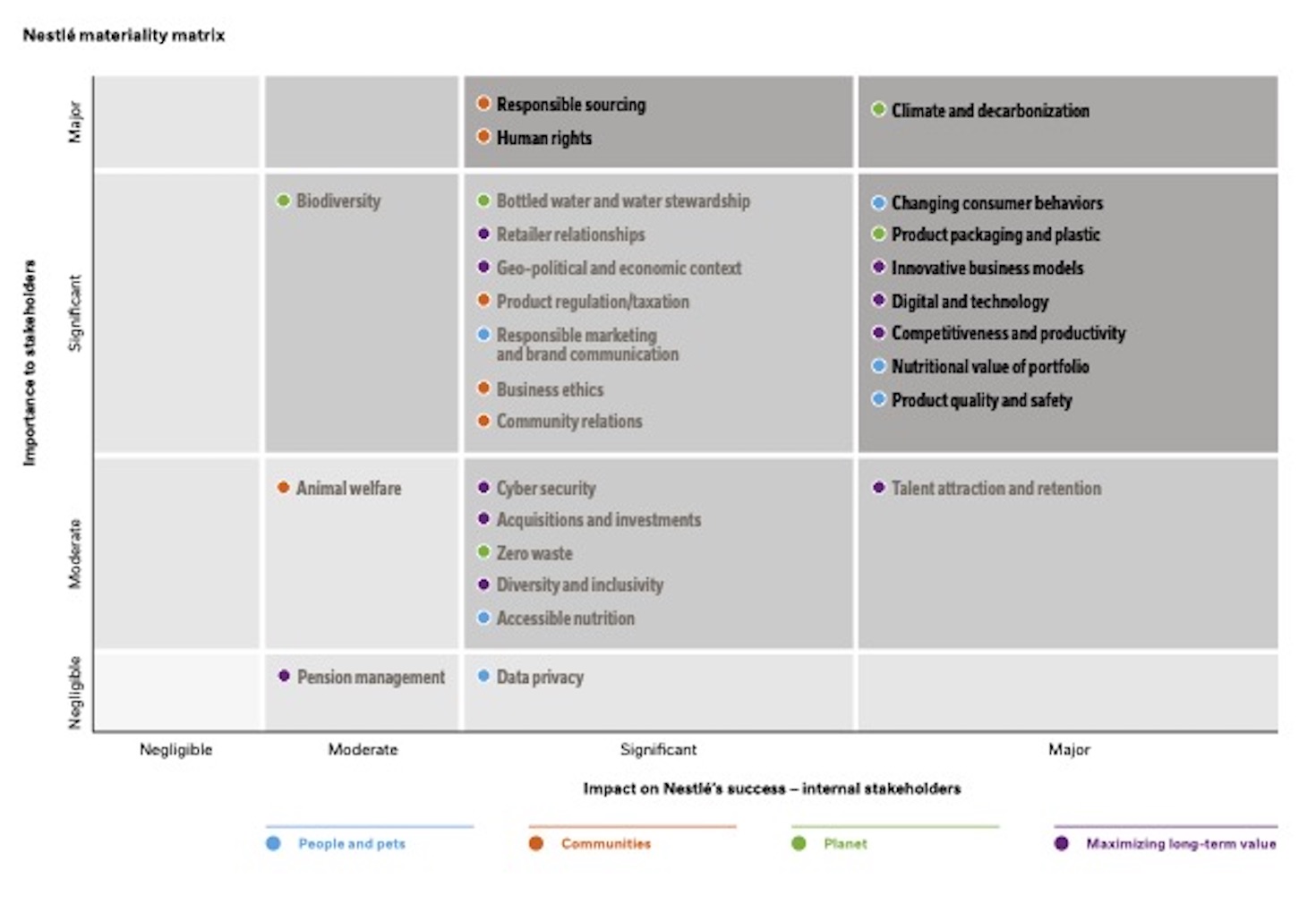

Clearly, stakeholders are not a monolith — they most likely will rate different ESG issues differently. This can be addressed through the weighting done under stakeholder mapping, or more informally by the company’s own best assessment. Creating a materiality matrix is a data-driven art, not a science, and the results will vary significantly even for similar companies within the same sector. CSB’s Sustainability Materiality Matrices Explained provides more insight into the topic. To get an understanding of how similar businesses may have different analyses of materiality, take a look at the Unilever 2020 materiality matrix presented below in Figure 1 and that of Nestle (Figure 2), a similar business. Note the similarities and differences in both the issues and their placement. For example, Unilever has fewer issues listed. Both companies focus on climate change and packaging as significant risks. Nestle rates nutrition slightly higher in importance to the business than Unilever, while Unilever rates water slightly higher. They both rate animal welfare and biodiversity as important, but more important to stakeholders than to their businesses.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The materiality matrix should not just be a picture of current challenges but should capture material trends. It will need to be adjusted every two years, if not annually, in order to keep up with fast-moving developments in sustainability. Its function is to provide the building blocks for the company’s sustainability strategy by facilitating a process for prioritizing what is most material for the company and stakeholders.

It’s worth reading Unilever’s summary of how it uses its materiality assessment, which begins, “An issue is material to Unilever if it meets two conditions. Firstly, it impacts our business significantly in terms of growth, cost or risk. And secondly, it is important to our stakeholders — such as investors, society (citizens, NGOs, governments), consumers, customers (retailers), suppliers and our employees — and they expect us to take action on the issue. In determining if an issue is material, we consider our impacts across the value chain.”

In conclusion, identifying and mapping material ESG issues for a business are the first building blocks in embedding sustainability core to business strategy, with the goal of ensuring positive impact and financial returns. Engaging and listening to stakeholders is a critical element in designing that matrix and strategy. Our next GreenBiz installment will detail how to map and engage stakeholders.

Editor’s note: This is part of a series about how companies can integrate sustainability into their core business strategies. The first article provides an overview of assessing current sustainability plans and the potential for embedded strategies to drive better management, financial performance and societal impact.

The post "The first step toward an embedded sustainability strategy: Pinpoint key ESG issues" appeared first on Green Biz

0 Comments