The coronation of Charles III inevitably brought renewed claims that monarchies are unwelcome relics of a bygone age. In at least one respect, though, the U.K.’s new king deserves to be recognized as ahead of the curve.

As Prince of Wales, Charles was avowedly green long before sustainability was fashionable. He gave his first major speech on the environment in 1970 and has championed various conservation causes ever since.

At Highgrove, his private residence, he established one of Britain’s first fully organic farms. He had his vintage Aston Martin converted to run on surplus wine and whey. In 1986, in an admission greeted with widespread ridicule, he even revealed how he would talk to plants to help them grow.

The merits of conversing with the natural world remain a matter of scientific debate to this day. Yet the merits of investing in it are becoming tougher to dispute.

Nature-based investments could prove to be the ultimate realization of these twin goals of ESG investing.

Historically, the argument for nature-based investments has often hinged on the fundamental notion of “doing the right thing.” This justification still holds: By channeling funds towards the safeguarding of ecosystems, we are protecting our planet and its inhabitants — ourselves included.

But what about the financial benefits? In the face of significant geo-economic and geopolitical uncertainty, more investors are at last beginning to understand why nature can represent an attractive long-term play on numerous levels.

Branching out

With quantitative easing making way for quantitative tightening, the days of easy money have finally come to an end. The inescapable reality is that it is harder to generate capital returns now than it has been for many years.

As a result, particularly for institutional investors, income is a greater consideration. Dividends from listed markets are perhaps the most obvious source, but private markets should not be overlooked.

It is private markets that offer the likeliest route into nature-based investments. This is in large part because such investments frequently demand highly specialized experience and expertise.

Take timber. It is well known that the sustainable management of forestry is vital to addressing issues such as climate change and biodiversity loss, but what is less appreciated is that this is an asset class with a solid record of delivering income for investors.

It is also capable of reducing sensitivity to market movements. Timber is a low-volatility investment, not just in comparison to private equity and listed equities but relative to the likes of real estate and infrastructure.

One reason for this is that timber is infinitely renewable. Every tree sequesters carbon from CO2 in the atmosphere as it grows, and sustainable management dictates that replacement trees should be planted whenever timber is harvested. By any standard, this is a virtuous circle. Little wonder that timber, like other nature-based investments, has already served as a useful inflation hedge.

Foundations for transformation

Ongoing investment in the responsible use of natural resources is driving a necessary shift from finite, toxic commodities to sustainable alternatives. Bio-based building materials — timber once again foremost them — are a classic example of progress in this regard.

“Mass timber” is the term used to describe solid, structural-load-bearing components that are typically made from multiple layers of wood. This kind of construction can lead to buildings capable of storing as much carbon as their conventional counterparts produce in emissions.

At scale, the impacts of such a dramatic inversion would clearly be far-reaching. From an investment perspective, they would also further underline that the transition to a genuinely green global economy constitutes the biggest growth opportunity witnessed.

Crucially, regulatory support for investments in carbon-sequestering assets is likely to intensify. This is especially the case in Europe, which — notwithstanding notable strides in the U.S. — continues to lead the way on ESG regulation.

By way of illustration, mass timber construction was central to a recent discussion of the European Union’s bid to attain carbon neutrality by 2050. The EU’s European Economic and Social Committee heard how innovations in this sphere are likely to be pivotal to “a sustainable and climate-friendly future.”

Meanwhile, the EU’s Forest Strategy for 2030 is among the European Green Deal’s flagship initiatives. Its proposed measures include encouraging the sustainable use of wood-based resources and incentivizing forest owners and managers to adopt practices linked to carbon storage and sequestration.

Fulfilling ESG’s ‘dual mandate’

Charles III recalls being condemned as completely mad when he first warned of environmental collapse. Times have changed. Watching his coronation, I was reminded that the most unwelcome relic of a bygone age today is not a king who talks to plants but a status quo whose innate contempt for nature invites ecological disaster.

Of course, as with any investment, success in this space is not guaranteed. In private markets it is always important to partner with firms that prize transparency and are pragmatic in their appraisals and valuations.

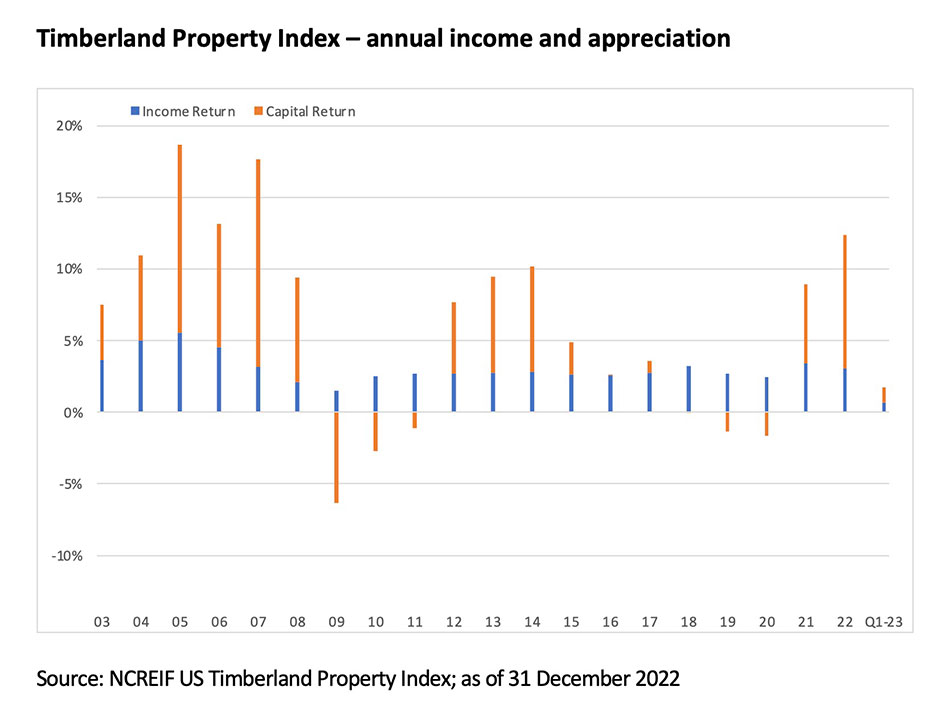

Yet the numbers increasingly speak for themselves. As shown in the figure below, which focuses on timber, the financial attractions of nature-based investments are by no means a novel phenomenon: the income element has endured over time while the capital return element has occasionally soared — including of late.

Investors might therefore wish to pay more attention to this arena. Its potential appeal has been heightened not just by the mounting urgency of global challenges but by the pressing need to diversify into resilient, uncorrelated investments amid a raft of new economic normals.

As we all know, the ideal “dual mandate” of ESG investing is inherently desirable and inclusive. It is to achieve good financial performance for investors and positive nonfinancial outcomes for as many stakeholders as possible.

Not least over the long term, nature-based investments could prove to be the ultimate realization of these twin goals. As such, they may yet come to be seen — rightly, in my opinion — as one of ESG’s crowning glories.

[GreenBiz publishes a range of perspectives on the transition to a clean economy. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the position of GreenBiz.]

The post "Why nature-based investments could be ESG’s crowning glory" appeared first on Green Biz

0 Comments